PKI & Trust Hierarchies

Browsers and devices trust a CA by accepting the Root Certificate into its root store – essentially a database of approved CAs that come pre-installed with the browser or device. Windows operates a root store, as does Apple, Mozilla (for its Firefox browser) and typically each mobile carrier also operates its own root store.

In SSL/TLS, S/MIME, code signing, and other applications of X.509 certificates, a hierarchy of certificates is used to verify the validity of a certificate’s issuer. This hierarchy is known as a chain of trust. In a chain of trust, certificates are issued and signed by certificates that live higher up in the hierarchy.

A chain of trust consists of several parts:

1. A trust anchor, which is the originating certificate authority (CA).

2. At least one intermediate certificate, serving as “insulation” between the CA and the end-entity certificate.

3. The end-entity certificate, which is used to validate the identity of an entity such as a website, business, or person.

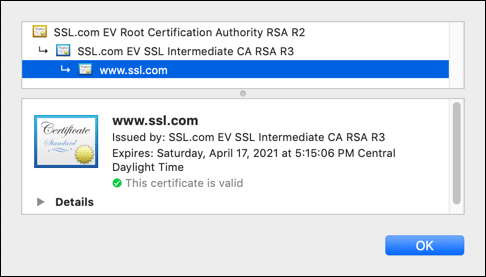

It’s easy to see a chain of trust for yourself by inspecting an HTTPS website’s certificate. When you check an SSL/TLS certificate in a web browser, you’ll find a breakdown of that digital certificate’s chain of trust, including the trust anchor, any intermediate certificates, and the end-entity certificate. These various points of verification are backed up by the validity of the previous layer or “link,” going back to the trust anchor.

The example below shows the chain of trust from SSL.com’s website, leading from the end-entity website certificate back to the root CA, via one intermediate certificate:

The root certificate authority (CA) serves as the trust anchor in a chain of trust. The validity of this trust anchor is vital to the integrity of the chain as a whole. If the CA is publicly trusted (like SSL.com), the root CA certificates are included by major software companies in their browser and operating system software. This inclusion ensures that certificates in a chain of trust leading back to any of the CA’s root certificates will be trusted by the software.

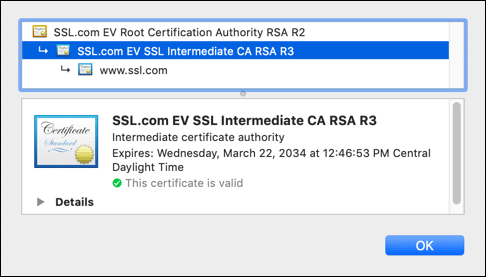

Below, you can see the trust anchor from SSL.com’s website (SSL.com EV Root Certification Authority RSA R2):

The root CA or trust anchor has the ability to sign and issue intermediate certificates. Intermediate certificates (also known as intermediate, subordinate, or issuing CAs) provide a flexible structure for conferring the validity of the trust anchor to additional intermediate and end-entity certificates in the chain. In this sense, intermediate certificates serve an administrative function; each intermediate can be used for a specific purpose — such as issuing SSL/TLS or code signing certificates — and can even be used to confer the root CA’s trust to other organizations.

Intermediate certificates also provide a buffer between the end-entity certificate and the root CA, protecting the private root key from compromise. For publicly trusted CAs (including SSL.com), the CA/Browser forum’s Baseline Requirements actually prohibit issuing end-entity certificates directly from the root CA, which must be kept securely offline. This means that any publicly trusted certificate’s chain of trust will include at least one intermediate certificate.

In the example shown below, SSL.com EV SSL Intermediate CA RSA R3 is the sole intermediate certificate in the SSL.com website’s chain of trust. As the certificate’s name suggests, it is only used for issuing EV SSL/TLS certificates:

The end-entity certificate is the final link in the chain of trust. The end-entity certificate (sometimes known as a leaf certificate or subscriber certificate), serves to confer the root CA’s trust, via any intermediates in the chain, to an entity such as a website, company, government, or individual person.

An end-entity certificate differs from a trust anchor or intermediate certificate in that it cannot issue additional certificates. It is, in a sense, the final link as far as the chain is concerned. The example below shows the end-entity SSL/TLS certificate from SSL.com’s website: